Will AI Augment or Replace Human Labor?

Spoiler Alert: it likely won’t matter.

I see a lot of writing on the topic of whether AI will enhance human intelligence and create new roles for human workers or replace human labor altogether, that leans strongly on “I feel” when discussing the likelihood of AI having a net positive or negative impact, often influenced by the author’s general personal tendency toward pessimism or optimism.

There are certainly reasons to be optimistic:

- AI can be used as a collaborator or assistant to amplify human labor

- New technologies tend to create new job roles and catagories

- AI is a powerful tool to support humans in learning new skills

But, if we are going to examine the likely impact on the demand for labor from this transformational technology, we should look at the data we have about the results of prior technological innovation.

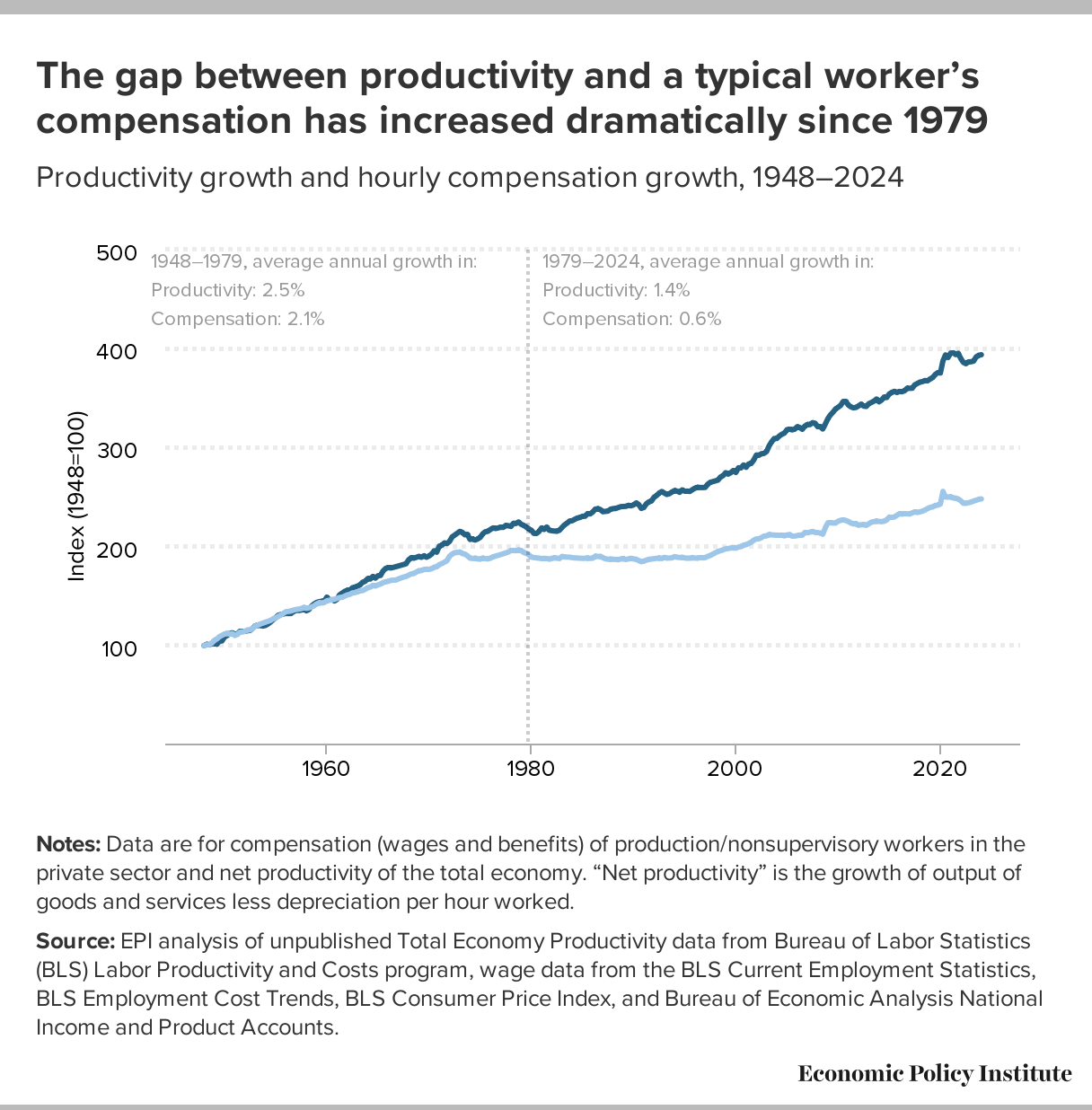

The Benefits of Increased Productivity

In 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that by 2030 workers would only need to work “three hour shifts or a 15 hour week” given the benefits of increased productivity from automation. Keynes suggested that this leisure bounty would be fueled by productivity gains of “four to eight times” in that period. JMK was spot on about the impact of automation on productivity, with BLS data showing 4-5x growth in productivity from 1947 to 2023 and 8-10x growth since 1930 as estimated in analysis by Robert J. Gordon in “The Rise and Fall of American Growth” (2016).

Keynes was less accurate in his forecast of how the gains in productivity would be shared. While productivity and wages tracked together reasonably well until the 1970s - meaning the gains in productivity were being shared with workers - they have since diverged dramatically.

I’m aware that there are many economic factors that have changed since the 1970s including the growth of global trade, the decline of labor unions and seismic shifts in the ability of corporations to influence public policy. So let’s just say that one of the other interesting things that happened in the 70’s and 80s was the development and commercializtion of computer hardware and software as tools to do some basic forms of thinking work - even if that thinking was mostly math and record-keeping and retrieval.

To put it more plainly, since the dawn of the information age, benefits from the growth in productivity due to the automation of mental or intellectual effort have not been shared with workers.

How much work can be automated with AI?

I think of any work that does not involve the creation, manipulation or transport of phyical goods (matter, atoms) as information work. Claude (3.7 Sonnet) and I estimate that in the U.S. that amounts to about 60-65% of all workers.

- Professional and business services (~20% of employment)

- Financial activities (~6%)

- Information sector (~2%)

- Most government workers (~15%)

- Education and health services, excluding hands-on healthcare providers (~10%)

- A portion of other service sectors that focus on information processing (~7-12%)

The remaining 35-40% includes manufacturing, construction, transportation, hands-on healthcare, agriculture, mining, and retail roles that involve physical manipulation of objects. (I’m not trying to nail the number, just establish a basis for discussion.) So, included in our estimate would be writers, lawyers, programmers, therapists, accountants and most ‘managers.’ It would also include physicians who are diagnosticians, but not surgeons.

Whatever you call the stuff you do in the middle (thinking, analyzing, creating, deciding, planning, innovating) if your inputs and outputs are bits not atoms, you are an information worker and AI can do an appreciable and rapidly-expanding chunk of what you do. I would argue (though I’m not going to) that the frontier models are already intelligent enough to do a better job at a majority of what information workers do, but there is more to actually replacing workers with AI than intelligence. There are processes and norms and systems and trust and a bunch of other momentum in organizations that will change more slowly than intelligence. In fact a good chunk of the intelligence that next-gen AI brings will likely be used for reengineering the way work gets done, not just for replacing humans with AI counterparts. The outcome, however will be the same.

Answering the question

Let’s get back to the question at hand: will AI replace or augment human labor? You’ve probably read some version of, “I don’t know if AI will replace human workers, but a human using AI will replace a human that doesn’t.” Gosh, if I were a machine superintelligence trying to smooth my entry into the workplace, I definitely would have designed that slogan. If we consider AI as an essential tool to make us more productive, we will use it. And if it makes me 10x more effective, where will the benefits of that productivity accrue? If history is our guide, it will not be to me/us. At least not past the rapidly-shrinking near-term.

60-70% of business costs are labor (is a statement I should probably research because I have not sourced it in recent memory) but if true or even mostly true, every business executive with a fiduciary responsibility would be irresponsible if they did not take advantage of a technology that reduced their largest operating cost by 50%. On an even more disheartening tip, the current (February 2025) business/social climate is one where tech leaders have decided that their employees who were so recently their “biggest competetve advantage” are now “holding them hostage” and “stealing my company” from me. People are a pain in the butt, they need to be motivated, they get sick, they have opinions, and those shifty working-from-home SOBs are probably on tiktok when they should be working. 50% fewer employees = 50% fewer problems.

In Conclusion

Historically, gains from automation have not been shared with employees. This has been increasingly true since the development and commercialization of computing. A large chunk of work today is information ‘processing.’ AI represents a nearly inexhaustable supply of knowlege, unprecedented fluency and super-human stamina, and like all prior information technologies, the price of a unit of compute is steadily falling. Humans are expensive and unpredictable. Business leaders are incentivized by the size of their profits, not the size of their payroll.

Unless we decide to make some significant changes in the system that is driving responsible corporate leaders to maximize proft and minimize workforce participation in the productivity that AI will bring, I see no historical precedent that justifies my own, or others irrational optimism.